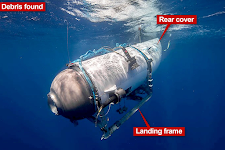

A 22-foot submarine dubbed Titan went missing on a voyage to survey the Titanic wreckage on Sunday. There were five persons on board. Authorities conducted a desperate search of the seafloor, covering an area the size of Massachusetts, as the sub's oxygen supply ran out. Rescue ships used sonar to scan the ocean for the shape of the vehicle and listened for it using microphones.

The US Coast Guard has now stated that a remotely operated vehicle discovered the Titanic's debris on the seafloor, 1,600 feet from the bow, at a depth of 12,500 feet. "The debris is consistent with the catastrophic loss of the pressure chamber," said Coast Guard Rear Admiral John Mauger during a press briefing at the Coast Guard's Boston facility.

The vessel's nose cone was discovered first, followed by a massive debris field containing the pressure hull's front end bell. "That was the first indication that there was a catastrophic event," said Paul Hankins, the US Navy's salvage supervisor. The search crews then discovered a tiny debris field near the other end of the pressure hull. Mauger went on to say that the remotely driven vehicles would remain on the scene to collect evidence.

OceanGate, the sub's operator, confirmed the vessel's loss in a statement: "This is an extremely sad time for our dedicated employees who are exhausted and grieving deeply over this loss." The entire OceanGate family is appreciative to the innumerable men and women from various organizations throughout the international community who have expedited extensive resources and worked tirelessly on this endeavor." A request for additional comment was not immediately returned by the corporation.

According to Mauger, the debris shows that the truck collapsed, however investigators are unsure when this occurred. According to Mauger, the rescue mission has had sonar-equipped buoys in the water around the Titanic's ruins for 72 hours and did not detect the implosion, meaning it occurred earlier. The pressure at this depth is remarkable, at roughly 5,500 pounds per square inch—more than 360 times the hydrostatic pressure that people face at sea level. "Death would have been instantaneous," veteran US Navy physician Dale Mole told the BBC.

"Even though this has had several successful dives, things fatigue," says Jules Jaffe, a research oceanographer at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. "So my theory is that after several dives, the material's strength began to deteriorate, and that this occurs more in the joints than in the actual surfaces."

If you're onboard an airplane and the hull is breached in any way, such as an emergency door falling off, the captain can still safely land the plane. However, at 12,500 feet deep in the ocean, the pressures are so high that a breach does not simply allow water to enter. It results in the vessel's catastrophic failure. "It's toast," Jaffe says. "The discovery of fragments certainly supports the conclusion that there was a hull rupture." As far as I'm concerned, there are no other options."

According to the Marine Technology Society's database, which was last updated in 2020, there are 38 manned underwater vehicles in the world. The OceanGate submersible was an exception in this tiny group: It was designed to go down to depths of 13,120 feet. Most tourist submersibles, which typically operate around coral reefs, aren't classified as "manned underwater vehicles" because they only travel to depths of 150 feet or less, according to William Kohnen, a member of the Marine Technology Society who runs a submersible engineering firm.

Members of the group were concerned that the Titan submersible's design did adhere to industry safety requirements, and that OceanGate had not enlisted the services of a third party to validate their safety program. It is unknown whether OceanGate addressed the group's concerns.

The future of submersible tourism is uncertain now that the industry's spotless safety record has been shattered. However, Jaffe believes that undersea exploration will continue, particularly for oceanographers collecting vital seabed data. "The Challenger exploded. "When we saw that, we were all tragically depressed," Jaffe adds, referring to the 1986 Space Shuttle catastrophe. "But we got over it and built spacecraft that didn't."